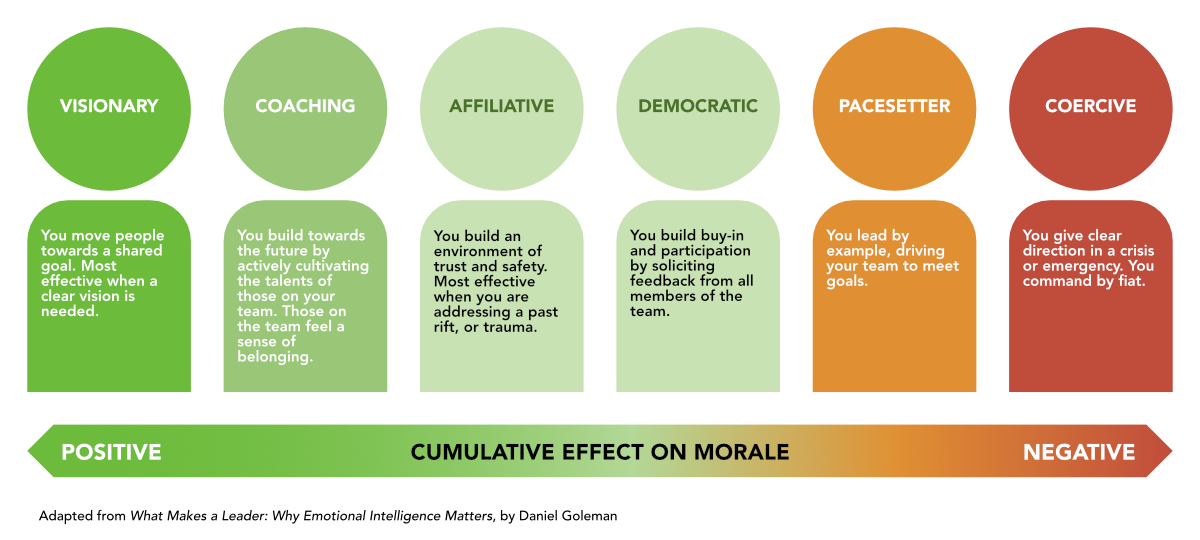

Leaders who have mastered four or more leadership styles – especially the visionary, democratic, affiliative, and coaching – have the very best climate and business performance.

And the most effective leaders switch flexibly among the leadership styles as needed. Such leaders don’t mechanically match their style to fit a checklist of situations – they are far more fluid.

They are exquisitely sensitive to the impact they are having on others and seamlessly adjust their style to get the best results.

Fluid Leadership In Action

Consider Joan, the general manager of a major division at a global food and beverage company. Joan was appointed to her job while the division was in a deep crisis. It had not made its profit targets for six years; in the most recent year, it had missed by $50 million. Morale among the top management team was miserable; mistrust and resentments were rampant.

Joan’s directive from above was clear: turn the division around. Joan did so with a nimbleness in switching among leadership styles that is rare. From the start, she realized she had a short window to demonstrate effective leadership and to establish rapport and trust. She also knew that she urgently needed to be informed about what was not working, so her first task was to listen to key people.

During her first week on the job she had lunch and dinner meetings with each member of the management team. Joan sought to get each person’s understanding of the current situation. But her focus was not so much on learning how each person diagnosed the problem as on getting to know each manager as a person. Here Joan employed the affiliative style: she explored their lives, dreams, and aspirations.

She also stepped into the coaching role, looking for ways she could help the team members achieve what they wanted in their careers. She followed the one-on-one conversations with a three-day off-site meeting. Her goal here was team building, so that everyone would own whatever solution for the business problems emerged. Her initial stance at the offsite meeting was that of a democratic leader. She encouraged everyone to express freely their frustrations and complaints.

The next day, Joan had the group focus on solutions: each person made three specific proposals about what needed to be done. As Joan clustered the suggestions, a natural consensus emerged about priorities for the business, such as cutting costs. As the group came up with specific action plans, Joan got the commitment and buy-in she sought.

With that vision in place, Joan shifted into the authoritative style, assigning accountability for each follow-up step to specific executives and holding them responsible for their accomplishment.

Over the following months, Joan’s main stance was authoritative. She continually articulated the group’s new vision in a way that reminded each member of how his or her role was crucial to achieving these goals. And, especially during the first few weeks of the plan’s implementation, Joan felt that the urgency of the business crisis justified an occasional shift into the coercive style should someone fail to meet his or her responsibility. As she put it, “I had to be brutal about this follow-up and make sure this stuff happened. It was going to take discipline and focus.”

The results? Every aspect of climate improved. People were innovating. They were talking about the division’s vision and crowing about their commitment to new, clear goals. The ultimate proof of Joan’s fluid leadership style is written in black ink: after only seven months, her division exceeded its yearly profit target by $5 million.

Develop Your Leadership Repertory

Few leaders, of course, have all six styles in their repertory, and even fewer know when and how to use them. In fact, as these findings have been shown to leaders in many organizations, the most common responses have been, “But I have only two of those!” and, “I can’t use all those styles. It wouldn’t be natural.”

Few leaders, of course, have all six styles in their repertory, and even fewer know when and how to use them. In fact, as these findings have been shown to leaders in many organizations, the most common responses have been, “But I have only two of those!” and, “I can’t use all those styles. It wouldn’t be natural.”

Such feelings are understandable, and in some cases, the antidote is relatively simple. The leader can build a team with members who employ styles she lacks.

Take the case of a VP for manufacturing. She successfully ran a global factory system largely by using the affiliative style. She was on the road constantly, meeting with plant managers, attending to their pressing concerns, and letting them know how much she cared about them personally.”¨ She left the division’s strategy – extreme efficiency – to a trusted lieutenant with a keen understanding of technology, and she delegated its performance standards to a colleague who was adept at the authoritative approach. She also had a pacesetter on her team who always visited the plants with her.

An alternative approach is for leaders to expand their own style repertories. To do so, leaders must first understand which emotional intelligence competencies underlie the leadership styles they are lacking. They can then work assiduously to increase their quotient of them.

For instance, an affiliative leader has strengths in three emotional intelligence competencies: in empathy, in building relationships, and in communication. Empathy – sensing how people are feeling in the moment – allows the affiliative leader to respond to employees in a way that is highly congruent with that person’s emotions, thus building rapport. The affiliative leader also displays a natural ease in forming new relationships, getting to know someone as a person, and cultivating a bond.

Finally, the outstanding affiliative leader has mastered the art of interpersonal communication, particularly in saying just the right thing or making the apt symbolic gesture at just the right moment. So if you are primarily a pacesetting leader who wants to be able to use the affiliative style more often, you would need to improve your level of empathy and, perhaps, your skills at building relationships or communicating effectively.

As another example, an authoritative leader who wants to add the democratic style to his repertory might need to work on the capabilities of collaboration and communication.

Hour to hour, day to day, week to week, executives must play their leadership styles like golf clubs, the right one at just the right time and in the right measure. The payoff is in the results.

Excerpt from Daniel Goleman’s book, What Makes a Leader: Why Emotional Intelligence Matters.